The Revolt of the Sergeants, The Cuban Revolution of 1933

The Revolution of 1933 was a turning point in the political situation of a constantly evolving Cuba. It brought to life, this sense of Cuban Nationalism and restrained influence from the United States in Cuban affairs, as well as putting together a new progressive social legislation. In Cuba, from 1930 to 1933, the country was engulfed in a violent political upheaval, led by the Student Revolutionary Directorate and a secret political organization, known only as ABC.

HISTORY

bishop

Gerardo Machado and his authoritarian policies, combined with the economic fallout of the Great Depression, sent Cuba into a whirlwind of economic instability and a social crisis causing various different groups to rise at a wild rate.

The Revolution of 1933 was a turning point in the political situation of a constantly evolving Cuba. It brought to life, this sense of Cuban Nationalism and restrained influence from the United States in Cuban affairs, as well as putting together a new progressive social legislation.

In Cuba, from 1930 to 1933, the country was engulfed in a violent political upheaval, led by the Student Revolutionary Directorate and a secret political organization, known only as ABC, combined with the brutal tactics of suppression, felt from the government through its military arm.

In an attempt to stabilize the situation, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dispatched his most trusted aide, Sumner Welles, to Havana in order to secure a peaceful resolution to the country’s political turmoil. Arriving as a mediator, eventually Welles was able to get Machado to concede to US influence and undermined the army’s loyalty to him, as well as restoring some confidence in the people.

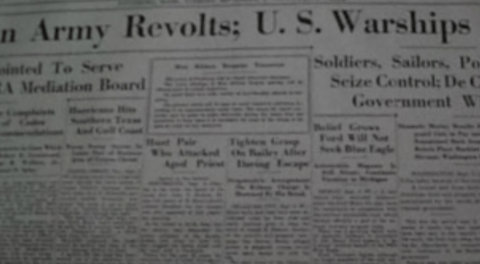

In August 1933, the country was paralyzed due to a general strike, and fearing a U.S. intervention, the army turned on Machado, forcing him to leave the island. Following Machado’s departure, Sumner Welles instituted a provisional government to fill the void, with Carlos Manuel de Céspedes del Castillo as President, and it was initially supported by the Student Revolutionary Directorate and the ABC. However, it would not last as the Student Directorate rejected Welles’ good will and in September, created a mutiny of army sergeants, led by none other than Fulgencio Batista into a revolutionary takeover. All military officers were removed and replaced with Sergeants and the provisional government was replaced with a new government as Ramón Grau San Martín, a physician and professor at the University of Havana, to assume the presidency in Cuba.

The Conspiracy of the sergeant revolt was initiated from the meeting of a group called the Junta of the Eight (J8). The group included Batista and other members of the ABC cell, which Batista was a part of, as well as an individual named Pablo Rodriguez, who was perceived by some as the actual group leader but would eventually be removed.

The J8 began meeting at the Columbia barracks in Havana and formed the Columbia Military Union with the idea of improving conditions in the army, which later turned into an expansion of their plans, targeted for a regime change in Cuba. On August 19th, 1933, a funeral service for Sergeant Miguel Ángel Hernández y Rodríguez, a Cuban army sergeant who was captured by the Machado government and killed, provided the platform for Batista to give a very passionate speech, and secured him enough attention and secured his role as a leader. Journalist Sergio Carbó, who was at the funeral, began interacting with Batista and became his voice to the world.

The sergeants were eventually able to create a manifesto, after the death of Sergeant Rodriguez, which called for dignity, respect, and benefits for soldiers, and declaring the duty of soldiers to rebel against the government. Batista, as a member of the ABC, asked the group to publicize the manifesto for them. The ABC denied his request, and prompted a mass exodus from the group, including Batista.

Mostly unknown to people today, the sergeants were not the only factions within the military that had been plotting against the government in Cuba, during this period of time. There were other groups who were even outwardly spoken against it. As the movement grew, these proto-Cuban revolutionists were meeting in large venues such as the masonic Gran Logia de Cuba and at the military hospital in Havana. Though the meetings were becoming overwhelmingly obvious, they continued to grow in popularity.

On the 3rd & 4th of September, non-commissioned officers at the Columbia Barracks in Havana, began questioning their commanding officers over topics such as back pay and promotions for enlisted personnel.

One of their captains, Captain Torres Menier, appeared to the group on the 2nd day, at a meeting at the Columbia Barracks. Batista allowed him to enter the room and permitted him to talk to the group. The complaints of the enlisted men came at a enthusiastic and boisterous pace. Menier withdrew from the room with the promise to consult the superior officers.

Another meeting was called for 8pm that night at a local theater, excluding the senior officers. The journalist Sergio Carbó, whom Batista had already secured confidence in, was there as well as Juan Blas Hernández, a known rebel whom was already known for opposing Machado.

Below is what Batista said on stage at the theater that night, thus beginning the revolt of the sergeants:

SPANISH: De ahora en adelante, no obedezcas las órdenes de nadie más que las mías. Los sargentos primeros deben tomar inmediatamente el control de sus respectivas unidades militares. Si no hay sargento primero, o éste se niega a tomar el mando, debe hacerlo el sargento mayor. Si no hay sargento, cabo. Si no hay cabo dispuesto, entonces un soldado, y si no, entonces un recluta. Las unidades deben tener una persona al mando y debe ser un soldado raso. ENGLISH: From this moment forward, do not obey anyone’s orders but mine. First sergeants must immediately take control of their respective military units. If there is no first sergeant, or if he refuses to take command, the senior sergeant must do so. If there is no sergeant, a corporal. If there is no willing corporal, then a soldier, and if not, then a recruit. The units must have someone in command and he must be an enlisted man.

Fulgencio Batista | Revolt of the Sergeants | Cuba, 1933

From that point forward, the sergeants took control of the Columbia Barracks and were uncontested in their control and soon established communications to sympathizing officers in other cities.

President Céspedes had been away from Havana during all the uprising on September 4th. It is unknown if the revolt was planned to align with the absence of the president; however, the timing worked in the favor of the revolting sergeants. On September 5th, the president arrived back in Havana and the J8 went to pay him a visit. The J8 proceeded to inform him that they had in fact seized control of the government and he was no longer in control. When the J8 informed him of their unwavering control of the military, President Céspedes fled the Presidential Palace with no contest.

The J8 along with the student directorate, proclaimed that it had control in order to fulfill the needs of the revolution, briefly outlining a government structure which claimed a basis of justice and democracy. It included economic, judicial, and political restructuring as well as acknowledgement of public debt and adjustments to the criminal penal code for what it considered criminal. The soon to be president Ramón Grau and Fulgencio Batista went to see Sumner Welles on September 5th in order to seek support from the US and get a feel for his stance on the revolution.

5 days after the coup overthrew sitting President Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada, its new government led by a five-man coalition, known as the Pentarchy of 1933. Less than a week later, the Pentarchy dissolved, giving way to Ramón Grau being promoted to the presidency and Fulgencio Batista became the head of the Cuban armed forces.

Some 900 officers were removed from their commands and stripped of their commissions and rank. 300 officers went into either retirement, prison or exile and 200 rejoined the armed forces which were now under Batista’s control. The remaining officers went to the Hotel Nacional in Havana to await a return of their positions and the former government to power. The officers at the Hotel Nacional would be eliminated in what has come to be known as the Battle of the Hotel Nacional, where they were murdered by the consolidated power of the newly formed enlisted military under Batista.

The newly formed government would last only 100 days, and never gained any international diplomatic recognition, not even from the United States. It was overthrown in January of 1934, under pressure from the United States government who was pushing for Batista to take control.