The Meiji Restoration of Japan, 1868

FEATUREDHISTORY

BISHOP

It was not the rise of imperialism in Japan that the United States perceived as a threat. Imperial Japan posed the most imminent threat to China, a country which was still in its communistic infancy, that would show the most concern. And to understand this, we must go back to the Meiji Restoration to understand how Japan got to where it was on December 7th, 1941.

This is the other half of history that never gets brought to light but it is very important in order to understand how politics gets in the way of truth, and how nationality can be used as a political weapon. This is the story of Japan that the majority doesn’t want you to hear.

The period of time surrounding the restoration of control to Emperor Meiji, beginning in 1868 was a glorious time for Japan. Empirical abilities were restored, and the political system was brought under the control of the emperor, consolidating all power under him.

These changes led to enormous alterations to Japan’s political and social structure and extended throughout the late EDO period and the beginning of the Meiji era, during a time of rapid industrialization adopted from western change.

At the age of 14, he became the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, Emperor Meiji began his reign on February 3rd, 1867 and continued until his death in 1912. He is known as the first monarch of the Empire of Japan and presided over the Meiji Restoration, a period of time which saw a rapid acceleration in Japan as it underwent changes from an isolated feudal society to a world industrialized superpower.

Under the reign of Emperor Meiji, Japan would see the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate, the Samurai would be stripped of all power and reduced to romanticized story telling, industrial production would increase 10 fold, and Japan would come under the most intense period of western influence.

By the early half of the 1860s, the shogunate, who had the control of Japan, had been under several threats. Foreign powers were seeking influence in Japan, and many daimyōs were unhappy and disgusted by how the shogunate were handling affairs. Many young Samurai would meet in secret and speak against the ruling shogunate. These young Samurai, known as shishi or men of high purpose, respected Emperor Kōmei and sought for a direct violent fight to cure the societal problems which plagued Japan. While they advocated for death of all foreigners, they would eventually begin advocating for the modernization of Japan.

Meiji, who had been pronounced the crowned prince, while studying a classical education and a focus on waka poetry, saw the rise of a new shōgun in 1866, Tokugawa Yoshinobu. The new shōgun was known as a reformer and wanted to see Japan turned into a more westernized

society. Yoshinobu would be the final shōgun in Japan, and received intense defiance from the bakufu (Japanese military government).

At the age of 36, Emperor Kōmei became suddenly ill and died on January 30th, 1867. At a ceremony in Kyoto, Japan, the 14 year old crown prince ascended to the throne on February 3rd, 1867. During this period, Yoshinobu would struggle greatly to maintain power as the new Emperor would continue his studies. There is no clear sense on whether or not Emperor Meiji approved Yoshinobu’s actions; however, the shishi were continuing to mold Japan into their own new vision.

Yoshinobu would be caught in a desperate struggle against separatist rebels, and though Yoshinobu and the shishi revered the Emperor, they would not bother him with politics. The struggle came to a head towards the end of 1867, and Yoshinobu would keep his title and partial power, but the law-making branch of government would be handed to a legislative government based on the British House of Commons. The new agreement collapsed and Yoshinobu resigned his post on November 9th, 1867. The rebels would march on Kyoto in December and commandeer the imperial palace. Emperor Meiji then declared a return to Imperial rule on January 4th, 1868.

In February, the following notice was sent to all foreign powers:

"The Emperor of Japan announces to the sovereigns of all foreign countries and to their subjects that permission has been granted to the shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu to return the governing power in accordance with his own request. We shall henceforward exercise supreme authority in all the internal and external affairs of the country. Consequently, the title of Emperor must be substituted for that of Tycoon, in which the treaties have been made. Officers are being appointed by us to the conduct of foreign affairs. It is desirable that the representatives of the treaty powers recognize this announcement."

-Emperor Meiji

The Meiji Restoration and Modernization / afe.easia.columbia.edu / http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/japan_1750_meiji.htm / accessed on 10/22/2022

The Boshin War ( War of the Year of the Dragon )

Shortly after the ending of the Takugawa Shogunate, the Boshin War began which started with the Battle of Toba-Fushimi where Chōshū and Satsuma’s forces defeated the ex-shōgun’s army. All Tokugawa lands were confiscated and placed under imperial control and solidifying the new Meiji government.

Under the new government, Fuhanken sanchisei, the land was split into 3 different types of prefectures: urban prefectures, rural prefectures, and the already existing domains. In 1869, daimyōs of the Tosa, Hizen, Satsuma and Chōshū Domains were persuaded to return their domains to the Emperor. Other daimyōs were also persuaded, thus creating the central government in Japan which now had total control throughout the entirety of Japan.

Some shogunate forces fled to Hokkaidō, where they attempted to set up a new government called the Republic of Ezo, but it ended in 1869 with the Battle of Hakodate. The defeat of the shogunate armies was the last step in restoring imperial rule.

In 1872, all daimyōs were summoned before the Emperor, and it was declared that all domains had been returned to him. The 280 domains were converted into 72 prefectures, each under the control of an appointed governor. If the daimyōs agreed without contest, they were given a voice under the new Emperor’s government.

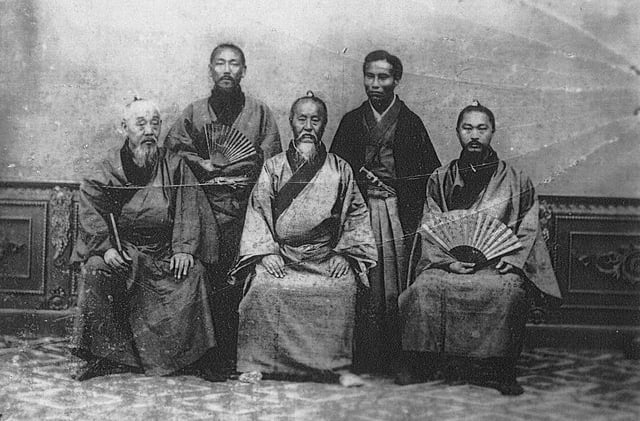

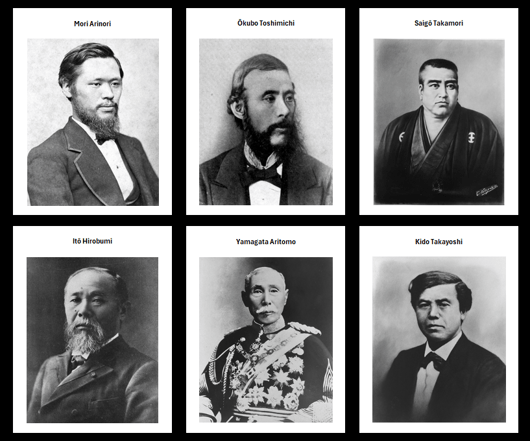

The Meiji Six Society

Led by Mori Arinori, a group of Japanese intellectuals called the Meiji Six Society began and continued to promote enlightenment and modernity in Japanese culture. This forced a move of political power which was formerly kept by the shogunate to a new oligarchy consisting of the Meiji Six Society.

Mori Arinori

From the Satsuma Province

Ōkubo Toshimichi

Saigō Takamori

From the Chōshū Province

Itō Hirobumi

Yamagata Aritomo

Kido Takayoshi

These Japanese oligarchs were instrumental in setting up under imperial rule, in reflection of their beliefs at the time, a more traditional practice where the Emperor of Japan served only as the spiritual authority and his ministers governed the nation.

They worked furiously to consolidate their power against the remnant of the Edo period shogunate, daimyōs, and the Samurai. They even went as far as starting the process of doing away with the four divisions of society which were the shi, the nong, the gong, and the shang, in their reformation.

The Samurai

Most think of the Samurai as being some ancient warrior, but in reality, it wasn’t that long ago. In the timeline of changes below, I’ve added the number of years prior to Pearl Harbor to illustrate how close in time it was.

The Samurai were the military nobility, and the profession was inherited from father to son, in Japan from the late 12th century until their abolishment in 1876. They were well paid, on retainer, by the local daimyōs. There was a high prestige in Japan for the Samurai, who also held special privileges such as Kiri-sute gomen which is the right to kill anyone of a lower class in specific situations, and they, unlike the rest of Japan, were allowed to carry 2 swords instead of just 1. They cultivated the martial art of bushido and its virtues, maintained an indifference to pain, and unwavering loyalty to their masters.

They were the Japanese equivalent of a European Knight of the medieval period. They emerged under the Kamakura shogunate, which ruled from 1185 – 1333, and from their inception, they were the political ruling class with significant power but also a significant responsibility. Proving themselves against the Mongols, they became stewards of society during the Edo era. By 1870, just 71 years prior to Pearl Harbor, the Samurai families held 5% of the population in Japan.

By the time of the Meiji Reformation, 1.9 million Samurai were in Japan. This was 10+ times the size of the privileged class in France, prior to the 1789 French Revolution. Kept by a high monetary retainer above all others, the oligarchs saw this as an unnecessary financial burden and chose to act against them.

1873 ( 68 Years Before Pearl Harbor )

Their wages were taxed on a rolling basis

Military conscription began for every male 21 years or older, followed by 3 reserve years

Every male was now allowed to carry weapons, which up to this time was only allowed for the Samurai

Samurai could no longer wear 2 swords, only 1, which blended them in with the other males and removed the Samurai from displaying status in public

1874 ( 67 Years Before Pearl Harbor )

The Samurai were given the option to convert their wages to government bonds

1876 ( 65 Years Before Pearl Harbor )

It became mandatory for the Samurai to be paid in government bonds

Though this led to rebellion and eventually civil war, the majority of Samurai were content with the abolishment of their class. They were not happy with the level of government bureaucracy that had been developed and simply wanted out. Many went on to become teachers, gun makers, government officials, and also military officers in the Imperial Japanese Army. The Samurai would eventually live on in a romanticized form in books and publications as well as propaganda for the wars of the 20th century.

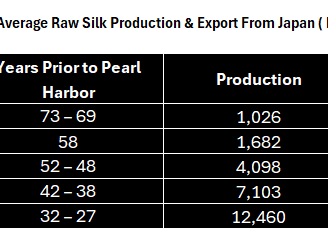

The Culmination of Industrial Growth 1895 ( 46 Years Before Pearl Harbor )

By the year 1895, 46 years before Pearl Harbor, The Meiji Restoration had accelerated the industrialization of Japan at a rapid pace. This led to the rise of Japanese power through the military under the slogan of “Enrich the country, strengthen the military” (富国強兵, fukoku kyōhei).

During the restoration process, the United States and other European countries helped and most often times led the changes which were happening there. One of the largest hurdles which Japan had to overcome was its lack of natural resources. The Meiji Six were instrumental in sending officials to foreign lands to understand new world technology and modernity, in an effort to implement these new processes in Japan.

This led to massive increases in production and infrastructure in the fields of shipyards for modern shipbuilding, iron smelting, and spinning mills. Once in place, they were then sold to well-connected and influential entrepreneurs. Through this, Japan quickly became a player in the international markets selling goods to foreign countries which led to the growth of enormous industrial zones and massive migrations to industrialized centers from the countryside. Peasant farmers were now becoming industrial workers. A national railway system and modern communication systems were also completed during this time.

Annual average raw silk production and export from Japan in tons / Wikipedia

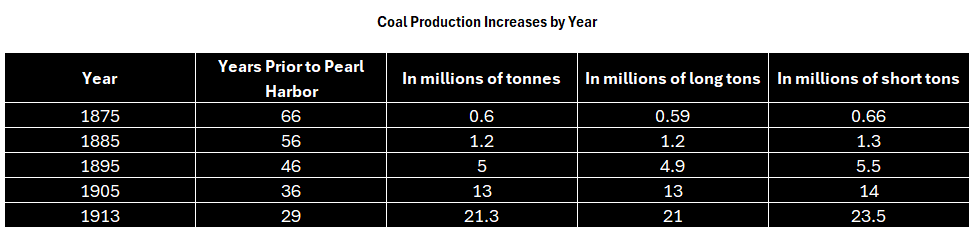

Coal Production Increases by Year / Wikipedia

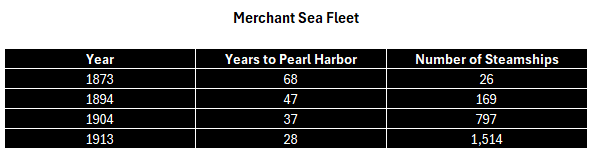

Merchant Sea Fleet / Wikipedia

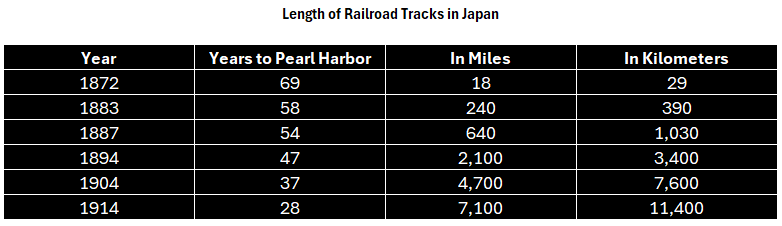

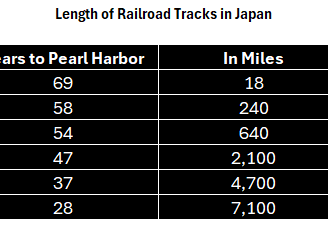

Length of Railroad Tracks in Japan / Wikipedia

During this westernization of Japan, its cultural infrastructure was virtually destroyed including Japanese castles, shrines, and Buddhist temples, in an effort to increase modernization.

The old religion of shinbutsu-shūgō where the Shinto gods were interpreted as manifestations of Buddhas, was completely abolished in a part of the Meiji Restoration called shinbutsu bunri (神仏分離), which was the separation of Shinto from Buddhism.

International Foreign Advisors to the Meiji Restoration

Throughout the Meiji Restoration, the western influence, which had grown widely during the enlightenment era, was key to the modernity of Japan. Enlightenment wasn’t simply going to be bound to the confines of western society, it was to take a global step, reaching the east.

Not only did the Meiji Six Society send people to foreign lands to learn of new ways and new technology, but specialists, advisors, and entrepreneurs were also in Japan influencing the country greatly.

In 1853, United States Navy Commodore William C. Perry arrived in Japan with his fleet. This fleet was known to the Japanese as ‘the black ships’ with armaments and technology, the likes of which they had never seen. Perry’s intent was to create a treaty for trade. Leaning to the ideal “if we take the initiative, we can dominate; if we do not, we will be dominated,” Japan welcomed the opportunity with open arms under leadership such as Shimazu Nariakira.

Officials in China, such as Chinese General Li Hongzhang, observing Japan’s initiative to grow with foreign influence, training, and technology, began to see Japan as China’s main threat to its security as early as 1863, 5 full years before the official beginning of the Meiji Restoration.

The leaders in Japan of the restoration process, acted in the re-establishment of imperial rule to empower the country and keep it from being colonized as well as ending the 250 year old foreign policy of assigning the death penalty to foreigners.

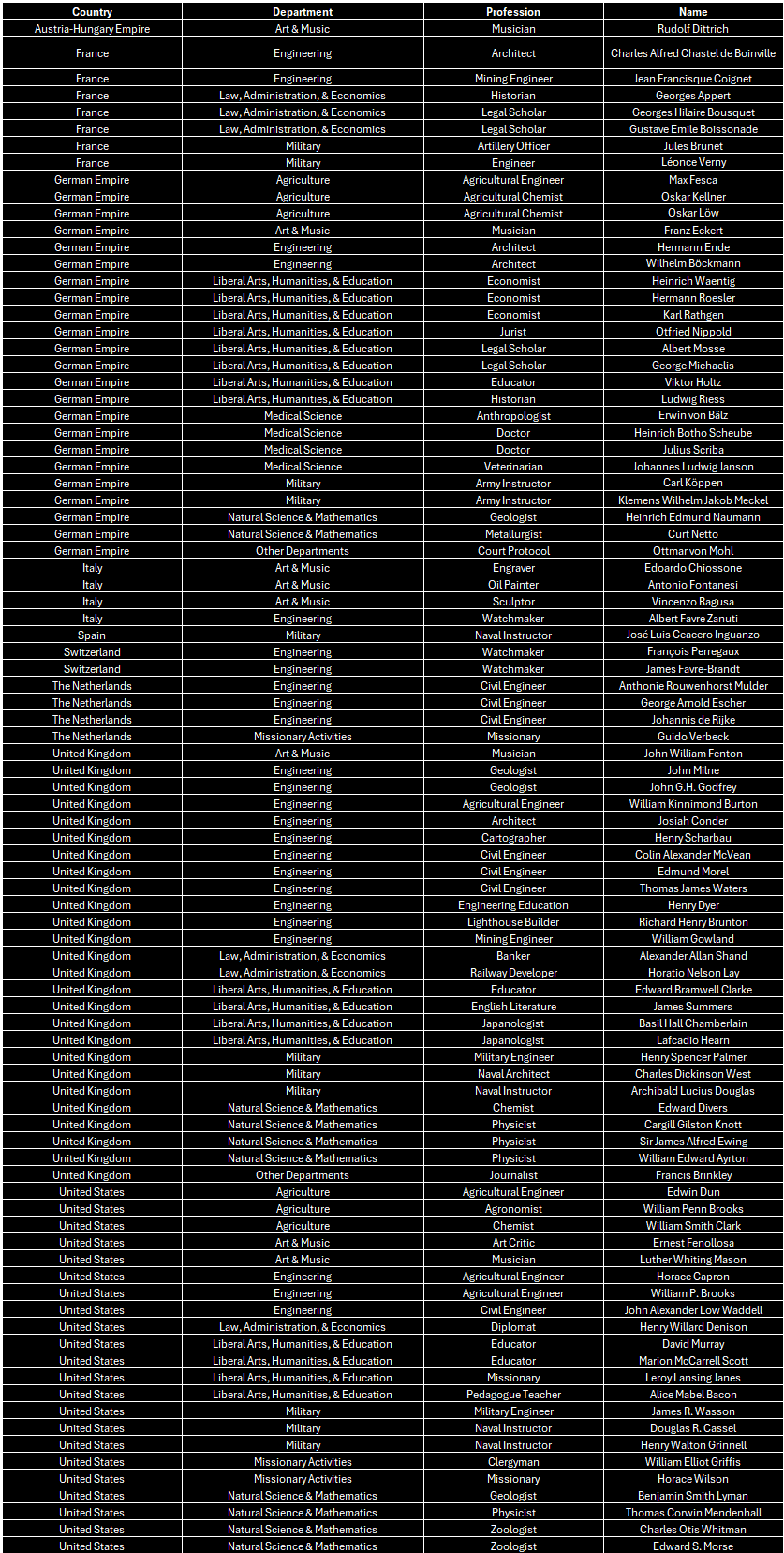

Here is a list of foreign advisors and specialists who were instrumental in the Meiji Restoration:

Even before the ending of the shogunate, Japan had already engaged in international requests to hire foreign advisors in an attempt to aid the country in modernization. One of the original foreigners to come was German diplomat, Philipp Franz von Siebold, as a diplomatic advisor. Other advisors would include Hendrik Hardes from the Netherlands to construct Nagasaki Arsenal and Willem Johan Cornelis, Ridder Huijssen van Kattendijke for the Nagasaki Naval Training Center. The majority of those contracted were hired through the Japanese Government for 2 – 3 year terms.

I will be making individual profiles on these advisors in the future, in an effort to understand who was influencing Japan prior to Pearl Harbor. But for now, there does indeed to be an international influence in the modernization of Japan.